by Finn Ruttan-Smith

Speculative fiction is an increasingly popular term used to describe a cross-section of fiction writing including science-fiction, fantasy and horror. Originally coined by Robert Heinlein in 1947, the name began as a term for a subset of science-fiction stories, narratives less concerned with science or technology themselves but rather the human reaction to these elements. As time has progressed, speculative fiction has led various authors or organizations to attempt to narrow or alter this definition. However, the central tenet of Heinlein’s definition seems to have stuck in the popular imagining of the genre, that being its very literary concern with the human element of storytelling. Even if a piece of speculative fiction has no “human” characters, it uses its story elements to speculate about our world and the people in it.

It is exactly this seed of the real within the unreal that has made speculative fiction by BIPOC authors so powerful and original in a field historically dominated by white men. Speculative fiction offers the opportunity to peer into a different world and see our own reflected back. It allows aspects of our real lives to be highlighted against a background of the unfamiliar and otherworldly. Issues that can get swept under the carpet in reality can be brought into stark focus when placed in a new setting. However, those reflections are only as powerful as the author can make them, and the dominance of writers of a certain demographic inevitably distorts the picture. The relatively recent boom in BIPOC speculative fiction writers is a step towards correcting this distortion, and allowing the contemporary spec-fic canon to be a more accurate representation of the struggles the world is facing in our time.

It is important to recognize that the current popularity of black speculative fiction writing did not emerge from a vacuum; examples of black writers creating stories that we would now call speculative fiction can be seen over the last century and beyond. The text commonly cited as the first African-American piece of published speculative fiction is Martin Delaney’s Blake; or the Huts of America, published serially beginning in 1859. It is a story of slavery and revolt involving a secret society known as the Oppressed Men and Women of Cuba and a desperate flight to Canada, spreading revolutionary idealism along the way. While it may not contain the level of speculation we often see today, later black speculative fiction writer Samuel R. Delany (no relation) calls Blake “proto-science fiction...about as close to an sf-style alternate history novel as you can get.” It is remarkable to see such an early use of the alternate-history trope, something that continues to see use today.

Prominent intellectual W. E. B. Du Bois, although best known for his contributions to sociology, also wrote a speculative fiction story called “The Comet” in 1920. It revolves around the relationship between a black man and a white woman after a comet hits New York, releasing a toxic gas which kills everyone but the two. Even a hundred years ago, speculative fiction was being used by remarkable people like Du Bois to analyze race and gender relations in a divided country. Later on in the 20th century, Samuel R. Delany used speculative fiction to explore linguistics and sexuality in his book Babel-17, a story about the weaponization of language and the power of words to alter the perception of certain groups. Delany’s book also won Best Novel in the second ever Nebula Awards in 1966, marking a significant landmark for the mainstream recognition of black speculative work.

In 1976, Octavia Butler reveals herself to the world. Through her portrayals of circumstances both alien and familiar, Butler cemented herself as one of the pillars of speculative fiction as a whole. Her work contains all the themes of gender, sexuality, race and perceptions of an Other that makes speculative fiction so effective at delivering cutting edge social commentary, and frequently pushes the boundaries of what feels safe or comfortable in relationships between very different peoples. Her short story “Bloodchild,” readable in her short story collection of the same name, explores the idea of male pregnancy through terrifying centipede-like aliens, and her more recent novel Fledgling uses vampires to address devotion, free will, and socially unacceptable love. Butler’s pathbreaking and prolific career certainly sets the stage for speculative fiction writers of the new millennium.

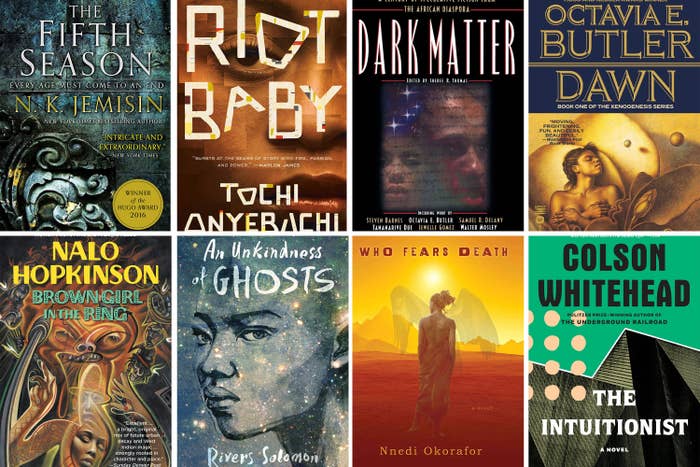

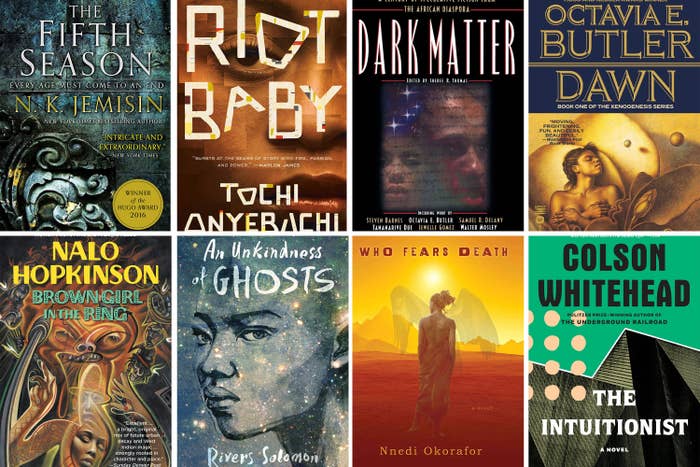

Today, the field of speculative fiction is more diverse than ever, and there are too many prominent and talented writers to be able to even scratch the surface here. Nnendi Okorafor stuns readers with her Binti series of novellas, stories of cross-cultural transmission in an intergalactic society. Nisi Shawl continues in the alternate-history tradition with her novel Everfair, set in the Belgian Congo, in which the native African peoples adopt steam technology as their own. N. K. Jemisin makes history with her triple award winning Broken Earth trilogy, skillfully incorporating narratives of oppression and power in with fascinating magic and ancient civilizations. With talent like these three and so many others working today, the future of speculative fiction looks bright indeed.

All this talk of social commentary is not at all to say that black writers, or any writers, cannot or do not write speculative fiction simply for the joy of creating new worlds and populating them with interesting characters. Octavia Butler herself once stated that her inspiration to start writing science fiction came from watching a B-movie, Devil Girl from Mars, and thinking “Geez, I can write a better story than that.”I only mean to highlight the important contributions black writers and other writers of color have made to the genre through variety of lived experience. Just as speculative fiction as a term has expanded to take on new dimensions and followers, black speculative fiction has developed in the same way. It is more exciting than ever to see where it will go next.